Reporting for Duty

The automatic doors of the hospital swoosh open as I grab my COVID-19 clearance and walk into the lobby. The security guard looks up with recognition, “You work here, right?” and waves me through. I shoot him a smile that signals that I know where I’m going. I head toward the back elevators as I’ve done time after time, I punch floor three and make my way through a familiar unit.

Knocking lightly on the door, I wring my hands with hand sanitizer from the mounted wall container and use my shoulder to push open the slightly ajar door. I announce myself as I enter with a cheerful tone and see the calm expression of a sleeping face. On the wall to my right is a row of light switches, I flick the one on the end, which brightly illuminates a fluorescent light above the headboard. I instinctually apologize and quickly flick it off, switching to another which casts more ambient light.

The patient doesn’t stir, “non-responsive to light,” I mentally note. I continue talking, increasing the volume of my voice, while acutely watching for the rise and fall of his chest. “Non-responsive to sound…. Is he still breathing?” Getting close to his chest, I listen for breath, faint and distance. His warmth surrounds me, his chest and arms soft as I embrace him.

Not hearing the next breath, I bolt out the door to the nursing station on the unit. A male nurse rushes to my side. With his stethoscope, he listens for a heart beat for a what feels like a long time before confirming that it’s still there.

Recognition that the Moment Has Arrived

My cool, calm, and collected “triage-mode” is overtaken by a crushing wave of emotion as I cry out in anguish, “Oh, Dad! I love you so much!”

The nurse listens again; I softly weep, squeezing Dad’s hand. I watch the caregiver’s every move, gathering through context that Dad has breathed his last. Leaving his earthly body, Dad delivers over his spirit. “Time of death – 8:11 p.m.,” I mutter as I glance at my cell phone. The nurse softly acknowledges, “You’re right, but we need a MD to officially call it.”

In another minute or two, a middle-aged man I’ve never met enters the room. The intensity of this moment is a lot to take in. I have begun to cry harder, catching my breath between sobs with tears streaming down and landing on Dad’s chest. The physician looks at me and says, “He was ‘do not resuscitate’.” “I know,” I quietly reply. “He was on hospice care. This was expected,” he continues. “I know,” I repeat. In this moment, I know these things are true and I have just lost my father. He excuses himself to give me privacy.

Mustering all the strength I had in me, I begin the process of notifying my family, beginning with calling my mom. It eerily feels a little like the moments after childbirth, calling your closest loved ones to announce that a new family member has just been born into the world, but in reverse. The anchor and patriarch of ours had just left it.

Finding Purpose in Life’s Most Important Roles

In life and in the workplace, we hear time and again that leadership has little to do with title. Whether a housekeeper or a CEO, we are told it is more about how you show up and conduct yourself than the actual work itself. But what if your title is simply – daughter. What if the role you find yourself thrust into is navigating the imminent loss of a parent, death, and the immediate aftermath.

Having just lived through it, on reflection it’s actually not that different at all. It seems like intentional leadership is all about doing your part, where you are, with what you have, infused with great love. Like most big decisions, you don’t have complete information at the point you need to make a call. You have to use the experiences and evidence you have to do what you think is right, putting others’ needs as high or higher than your own. And as you navigate one of life’s most challenging transitions, core values of empathy, compassion, patience, trust, and clarity couldn’t be more paramount.

Not pretending to be the perfect daughter, I share my experience to connect with others who have traversed this space and/or who will in the years to come. There is no roadmap for the death of a parent; neither leading up to it, nor how to move on afterwards. In hindsight, I feel incredibly lucky for the family I was born into, for the role my husband (and our au pair) played in taking care of my kids, and for the work I’d done processing my own emotions and coming to acceptance ahead of Dad’s death in the year(s) leading up to it. This combination allowed me to be more present to love and serve him and the family over the course of this precious week together.

Doing What You Can, Where You Are, With What You Have, With Big Love

With a depth of knowledge of end-of-life care and the brokenness of the system, I watched it unfold from halfway across the country. I learned to stifle my feelings of powerlessness by trying to focus on what I could do to support Dad and Mom from afar. I had a fair bit of healthcare knowledge. I was good at navigating complex systems. I had a very strong relationship with my mom built on a foundation of trust. Perhaps there was a lot I could do to help, despite the distance.

Sometimes it was healthcare literacy and explaining things, particularly when it came to insurance. Once it was researching and pointing Mom to North Dakota’s version of the eMOLST to clarify and document Dad’s end-of-life wishes. More often than not, it was reminding Mom that Dad’s health (and longevity) wasn’t in her hands, but God’s; trying to free her from any misplaced guilt.

Dad’s decline had been a long and slow one, drawn out over the course of years. The last two and a half had been particularly tumultuous with admissions to the hospital occurring once or twice a month. The only time these readmissions slowed were during stretches when Dad was in a subacute faculty (which he hated).

A pattern emerged where Dad would inevitably check himself out against medical advice, slamming shut each option available to him, one nursing home door at a time. On one notable occasion, my dad tried to “make a break for it” across a grassy field when his nurses weren’t looking. While he could have been outpaced by an infant crawling across the lawn, Dad’s behavior landed himself with an ankle tracker which only fed his rhetoric of being imprisoned.

Dad wanted to be at home. He clung to his independence as much as one can when you are that sick. He was a fighter and he knew what he wanted. Mom, in turn, was his faithful caregiver; taking on the true meaning of their time-tested wedding vows. She too was coming to the end of an unraveling rope, with her own health pitted unintentionally against his.

A Rollercoaster of Ambiguity

One to two-line emails from mom with bits of information addressed to me and my three siblings was how it began. Walking the line between not wanting to bother us (or perhaps alarm us), and wanting to keep us informed about Dad, little details trickled in. When these emails came in, I always wrote back to thank mom for the update, which in turn gave her the opening to share a bit more information on her reply. I try to call my mom almost daily, particularly on those eventful days when she’d email.

Knowing how much I craved additional information, I did my best to summarize and circulate what I learned to my other three siblings. Sometimes they already knew. Sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes some knew and others didn’t. Living the furthest away, it was really important to me that we all had the same information.

It hadn’t been too many days since Dad was last discharged. As per usual, he was adamant to be home. For the first time, mom started describing symptoms of “dementia.” She mentioned Dad was more “with it” at night than he was in the morning. On a check-in call, Mom shared that Dad kept calling for my sister and me (which was heartbreaking) asking if we’d left. The month prior, my sister and I had come home for our niece’s baptism and for us all to be together “one last time.”

Perhaps Dad was losing track of time and space? I read later in some hospice literature that this delusion isn’t uncommon at the end. Mom wasn’t sure if it were this or if he was backpedaling to the years of us growing up and living at home. Another day, Mom described Dad adamantly insisting that there were broken pieces of glass on the floor. She played along and picked them all up to get him off the topic and settled down.

Mom mentioned in passing that Dad had lost his appetite and was refusing to eat. She had entered into a bit of a bargaining arrangement with him to take x number of bites in return for his pain medication. Dad also seemed to lose interest in doing the things he loved, like going to the grain elevator to visit with a group of retired farmers or driving around and looking at the fields as harvest approached. Little by little, I began to wonder if this might be the end.

Being particularly out of it one night, Dad needed to go in. His kidney levels were elevated. In speaking to mom after the visit, she relayed that Dad had entered the final stages of kidney failure. Unless dialysis was on the table, which it wasn’t, his kidneys were not able to clear his blood effectively of his pain meds (which may be one explanation for the delirium) or of a blood infection he’d picked up on his last admission. I prodded mom a bit more on the blood infection. “Sepsis,” she reported.

Tapping Into My Posse

My heart sank in my chest. Having modeled high-risk, end-of-life patients at work countless times, this all sounded much too familiar. Knowing how virulent sepsis is even in the healthiest of individuals, my stomach turned over. I told my mom that I thought I should come. She emphatically said, “Don’t come.” He had been admitted last week and discharged a few days later. She wasn’t convinced that this was terribly different and encouraged me to give it time to see how things would play out.

Shortly after we hung up, I started bawling and looking for flights to Fargo where Dad was being driven to be admitted to the VA. Not knowing what to do, I turned to adults in my life that I respected who had lost parents. Surely a member of my leadership posse would tell me what to do! My first attempt was honest that she had no idea what I should do and hadn’t been in this situation before. We quickly hung up and I appreciated the gift of time back that evening to try another avenue.

Next I phoned my cousin, Leah, who was local (only a few miles from my parents) and who had been plugged into Dad’s health over the years. I had been the flower girl in her wedding as a child and loved and respected her immensely. Still, I hadn’t fully appreciated the role that Leah had played in her own parents’ deaths. Leah quickly shared some of her insights and experiences with me, and above all, gave me the space to be honest and vulnerable. Leah told me to trust my instincts and that I wouldn’t live with regret if I went and this time wasn’t the last time.

The Waiting

I doubled back to Delta.com. In the time I’d spent by phone, the price of the flight had skyrocketed north of $1,400 which felt cost prohibitive. I dug into Delta’s policy. If the family member had died, discounts were available, but in this scenario I was out of luck. I was exhausted. It was late. Not feeling well, I stumbled to the bathroom and vomited into the sink.

On her own accord, Leah and her husband, Barry, drove down to Fargo the next morning to visit Dad. She called me and confirmed that Dad had begun the dying process and was looking “through her” with glassy eyes. Leah advised that us kids should come now if we were going to come. I was able to speak to Dad’s nurse to get additional information and an estimation of the time Dad had left. Mom made her way to Fargo immediately. As Dad’s primary caregiver, she’d taken a short, much-needed break to rest up, but now was time to be present.

With Leah and Barry at Dad’s bedside, I asked to speak to my Dad. Over speaker phone, I reiterated how much I loved him. I told him I was coming and said goodbye for now. Then through text, I coordinated with each of my siblings to call and say anything they wanted to say to Dad that night. I booked the same flight I had looked at the evening before as a one-way ticket on miles. I would land at 10am the following morning. I called Leah back after everyone had gotten to say their goodbyes and asked if it might be ok for me to sing to Dad.

Getting a little bit vulnerable, I opened my hymnal and chose a few of Dad’s favorites. I could hear Leah sniffle a little as I sang. The night Dad died, one of his nurses brought me back to this moment and told me that it was the most calm she’d seen Dad since he’d been admitted.

A Pilgrimage

In the wee hours of the morning, I headed by car service to Newark, NJ. Miscalculating the time it would take to get an Uber at that hour, I almost missed my flight. Again in Minneapolis, in line to grab coffee during my layover, I found my lost-in-thought daydream interrupted by a last call announcement for “Enquist” to report to Gate B8. Still somewhat bleary-eyed, I ran to the gate to board.

My brother and sweet nephew met me at the airport. John had driven in the night before after talking to Dad by phone. He reported that his condition had not dramatically changed since his arrival and warned me about the scene I was about to walk into. For years, I’d played out scenarios where I was separated from my family at this moment given the physical distance I had to travel to get there. There was some sweetness and relief in being only the second child to report in. My sisters arrived within the next few hours.

We rotated through Dad’s room, watching and waiting. Anytime Dad called out in pain, I instinctively said “I love you, Dad” wishing I could take it all away. That night we gathered with Dad’s care team as a family to make final decisions on next steps. From my perspective, we were undeniably at the end. Dad was prepared to meet his maker, and I wanted his suffering to cease. We came to full agreement and moved exclusively to comfort care.

Holding Vigil

Exhausted, we all set out to a hotel to catch a few hours of sleep before the day ahead. Suspended in a window of time, we were booking rooms night to night unsure of what the next day would bring. Again, we rotated through, this time with Dad being more calm with moments of lucidity. When grandkids entered the room, he reacted with undeniable excitement.

Those of us who were not bedside gathered in a room designated for family. We began planning the service, unsure of the date given Dad was still with us. Mom expressed her strong desire to set up a scholarship fund in Dad’s name that she could award to college students in financial need. Stories of Dad were shared, both sentimental and ridiculous. He was our Dad after all.

Trying to make myself useful, and not being good at doing nothing, I researched how to set up a scholarship fund, which crowdsourcing sites had the lowest fees, and began the outline of the obituary. As the day wore on, those siblings who lived within driving distance and coincidentally had the youngest children (who had spent far too much time on a hospital ward) made plans for the coming days. My other sister from out-of-state turned to me, looking for guidance. “I’ll be here through the end,” I replied. Heading back to New York at this point wasn’t an option.

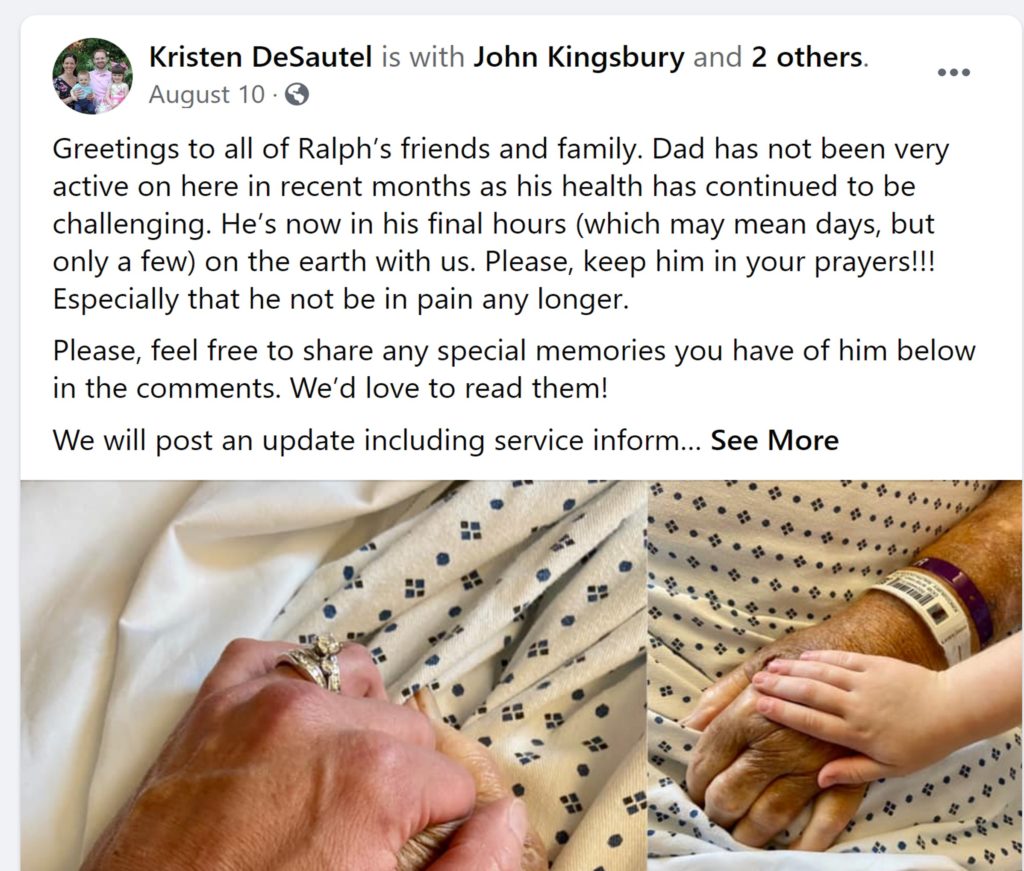

Before we left, one of my sisters posted an update to Facebook. She did it with all of our permission, tagging my Dad’s profile, my brother’s and mine. Not anticipating the emotional response I’d have to this news going public, I broke down in tears in a big way for the first time since I’d landed. Here we’d been in our own little bubble these last two days. It had been surreal, other worldly, almost outside of time and space. Now with “likes” and people’s comments pouring in, the grave reality of it all was sobering.

A Perfectly Timed Panic Attack

After beautiful goodbyes, two of my siblings headed out for a long drive. My eldest sister and I headed to yet another hotel as we continued our day-by-day planning. Mom headed home for some much needed rest. After checking in, we drove across town for a bite to eat.

Sitting outside the fast-food restaurant for what felt like eternity, I scrolled through the comments coming in on my sister’s post. Friends far and wide had responded. Fraternity brothers, fellow soldiers in Korean, farmers from Nash, and members of our large, tight-knit family had left messages for Dad. I pulled up the memories I’d transcribed from bedside stories with Dad from a year ago on his 77th birthday. Looking at pictures of him and I bedside, I had a visceral response to be near him that I can best describe as a mild panic attack.

The plan had been to stop by the grocery store across the street after dinner for breakfast options. While out-of-the-way, I pleaded with my sister if she’d be willing to bring me back to the hospital. I felt that I had to be with Dad in that moment and to hold vigil that night. She readily agreed and drove me over.

Reporting for Duty

The automatic doors of the hospital swoosh open as I walk into the lobby. The security guard looks up with recognition, “You work here, right?” and waves me through. I shoot him a smile that signals that I know where I’m going. I text my sister as this makes me laugh. I must give off a “hospital administrator” vibe.

Knocking lightly on the door, I announce myself as I enter with a cheerful tone and look at Dad’s peaceful smile. On the wall is a row of light switches, I flick the one on the end. Too bright! I apologize and quickly flick it off. Getting worried, I put my head on Dad’s chest, listening for breath. His warmth surrounds me, his chest and arms soft. I bolt out the door to the nursing station. With his stethoscope, the nurse listens for a heart beat for a what feels like a longtime, then confirms it’s still there. I text Kelly, “Dad’s dying!! Come back!!!”

I’ve been texting and calling non-stop on my phone to notify family when my best friend, Allison, calls me. I answer and place her on speaker phone. Kelly and her daughter have since joined me in Dad’s room. I am grateful for the company. Kelly knows Allison from our days at Notre Dame in the Folk Choir and since. Kelly suggests the old Irish hymn, “How Can I Keep From Singing,” as we usher Dad into eternity.

The evening continued in a blur of song, conversations with Dad as we wait for our mother to return, and Zooming our siblings into a beautiful Honor Escort where Dad is clothed in an Army flag and ushered out of his room to the sound of taps, with staff and Veterans saluting him on route to the morgue. Dad would have LOVED that!

Doing What You Can, Where You Are, With What You Have, With Big Love

It’s past midnight at the point we pull out of the hospital parking. As I lay my head down on my pillow, the adrenaline of entering Dad’s hospital room in his final moments replays over and over again in my mind. The next morning begins an all-out sprint to coordinate the details of my father’s funeral. Under very different circumstances, the logistical lift feels a bit like planning a wedding in three days. I’m a doer and being insanely busy proved to be an effective coping mechanism.

Supported by my tight-knit family, I tackled task after task that I’d never done before. My aunt and uncle’s WiFi was a life saver. Being able to work at their kitchen table, surrounded by laughter and sage advice made the days fly by. My husband held down the fort and my boss and team gave me the time and the space to mobilize on behalf of my dad. In turn, this allowed my mom the time and space she needed with her grandchildren to just be and begin to heal.

The day of Dad’s service, I sang my heart out for him. An old trick I learned to suppress tears, I counted the lights on the ceiling of the church before each piece. The service was beautiful, meaningful, and joyful. It was a celebration of a life well-lived.

As I said goodbye to my extended family to head to the airport, my cousin Joanna gave me a big hug that I’ll never forget. “Few people could have pulled that off…” If you would have told me even a week earlier, the role I would play leading up Dad’s death and immediately after, I wouldn’t have believed you. I would never have thought myself strong enough to endure it. Maybe Joanna was just being kind on the day of my father’s funeral, but it’s a moment I deeply treasure and always will.

I love you, Dad! Happy Heavenly Birthday! I’m so glad I was able to celebrate with you last year and to be holding your hand at the moment of your death. Thank you for waiting for me and allowing me the grace to have witnessed your passing into heaven.

“Do small things with great love.”

– Mother Teresa